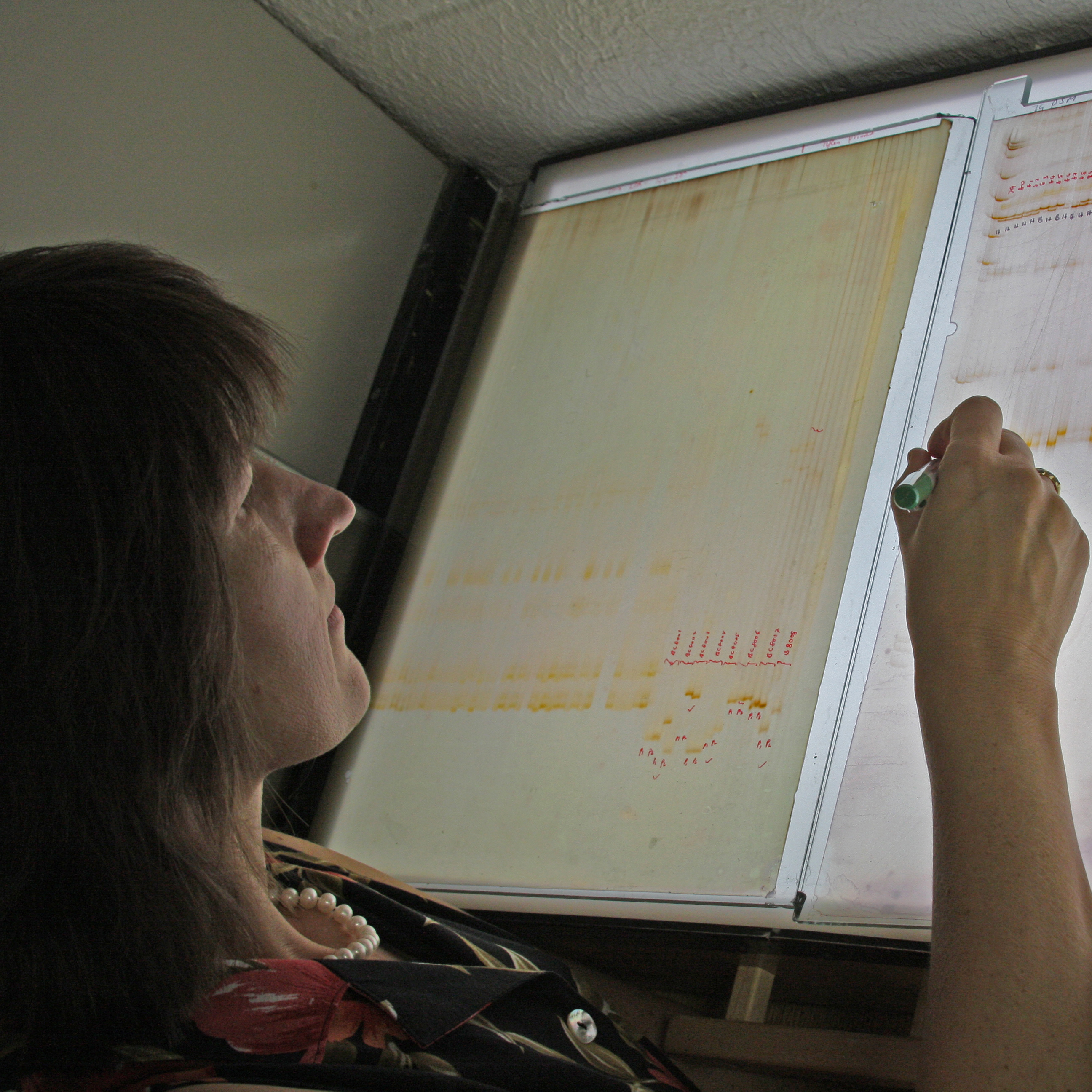

University of Georgia plant breeder and geneticist Katrien Devos’ work unraveling the mysteries of pearl millet aims to make subsistence farming communities more food-secure.

The pioneering and globally engaged nature of her work earned her one of UGA’s top research awards: the Creative Research Medal.

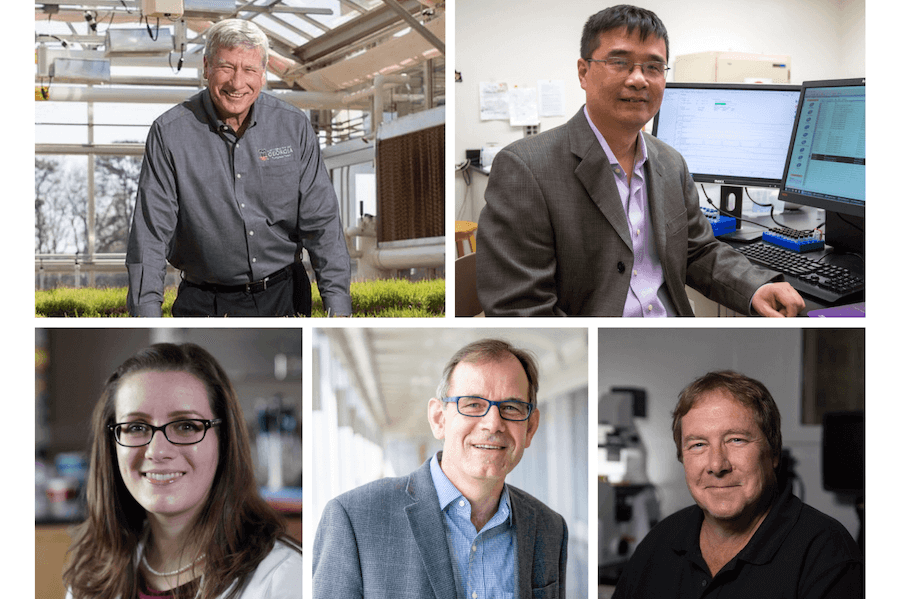

The Research Awards Program is sponsored by the UGA Research Foundation (UGARF). Awards are given annually to honor outstanding faculty, postdoctoral fellows and graduate students, and to recognize excellence in UGA research, scholarly creativity and technology commercialization.

A committee of accomplished researchers at UGA selects these award winners.

Devos, who holds a joint appointment in UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, earned her doctorate from Ghent University in Belgium. She conducted pioneering research on the comparative genetics of cereals at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, England, before coming to UGA in 2003.

In late 2016, Devos received a $1.8 million collaborative grant from the National Science Foundation to study the genetics of finger millet — an important crop that promotes food security in eastern Africa — and Magnaporthe oryzae, the fungal pathogen that causes blast disease in finger millet.

The resources developed through this project will help breeders create more efficient, sustainable varieties of finger millet that are also resistant to blast disease.

Recently, UGA plant geneticists successfully isolated the gene that creates dwarfed varieties of pearl millet. This is the first time that a gene controlling an important agronomic trait has been isolated in the pearl millet genome. Their work appeared in the March edition of the journal, G3: Genes, Genomics, Genetics.

The dwarf varieties are economically important in the U.S. and in India in particular. Dwarf varieties are used as forage plants in the U.S. and are grown as a food staple in India.

Devos’ team was able to trace the dwarf gene to plants bred 50 years ago by Glenn Burton, a UGA plant breeder who worked on CAES’s Tifton campus.

Knowing which gene controls the dwarfing trait will help plant breeders create more efficient, sustainable varieties of millet that have the short stature sought by some farmers and ranchers.

“Knowing the actual gene that reduces plant height has allowed us to develop markers that can be used by breeders to screen for the presence of the gene long before the effects of the gene can be visually observed,” Devos said. “In the longer term, the knowledge gained in pearl millet will help to develop semi-dwarf lines with high agronomic performances in other cereal crops,” she said.

Dwarf varieties of pearl millet are not ideal for every planting situation. In Africa, many farmers prefer taller varieties because they use the long stalks for roofing thatch and other applications.

However, dwarf millet allows farmers to harvest the grain with mechanical threshers where millet is intensively cultivated. Ranchers like dwarf millet as a forage plant because it has a high leaf-to-stem ratio, Devos said.

Knowing more about the plant is key to broadening production of the drought-resistant, hardy grain.

For more about Devos’ work, visit research.franklin.uga.edu/devoslab.