|

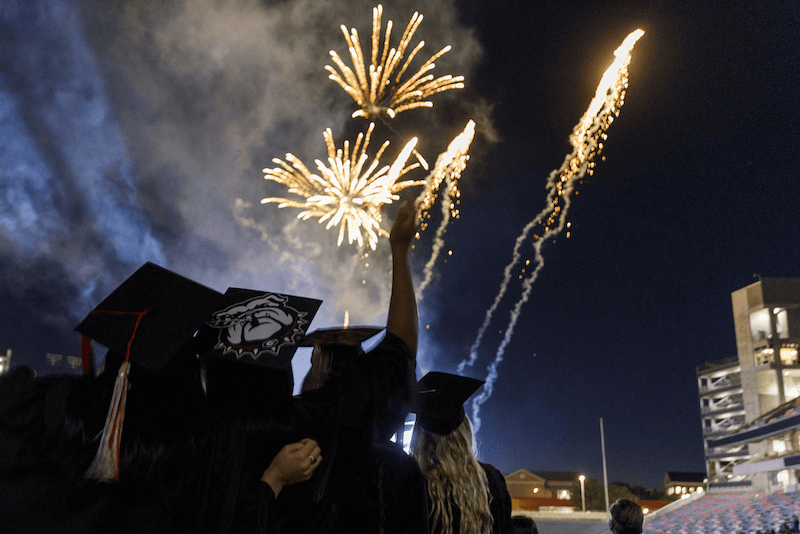

| With his portable spectral imaging system, Chi Thai is able to see plant health in a whole new light. |

The best time to treat a stressed plant may be just before you can see it's stressed. The trick is to know when that is. And a University of Georgia scientist may have the answer.

It's a matter of light, said Chi Thai, a biological and agricultural engineering scientist with the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

Plants, he said, are trying to tell us when they're stressed. We just can't see it.

It's not that we're not trying. Seeing that plants are stressed earlier than we normally do could save farmers millions of dollars. We just don't have the right equipment.

Human Eyes Limited

"Human eyes can see only at light wavelengths between 400 and 700 nanometers," Thai said. "For the part of light that gets through the atmosphere, the region of interest to our plant-health research is from ultraviolet wavelengths around 200nm to near-infrared wavelengths around 2500nm."

The answer, as Thai saw it, was to improve the equipment. "We've built a field-portable spectral imaging system," he said. "It contains two spectrometers sensitive from 300nm to 1700nm and is equipped with fiber optic inputs and continuously tunable spectral video imaging capability."

Thai adds some Liquid Crystal Tunable Filters, then a virtual-reality goggle (because a computer monitor is unwieldy in the field) to see plants in literally a whole new light.

Reading Plants' Chemical Signatures

"This equipment allows human users to visualize chemical signatures of a plant which usually are beyond unaided human vision," Thai said. The chemical signals let people see the plant's earliest signs of stress.

Thai took the process a step further, with an LCTF alternating between two fixed wavelengths, 692nm and 755nm. By plotting the average of the gray values of the pixels forming the plant canopy image, he can directly estimate the chlorophyll and biomass amounts in plants.

"The plant-health status was related to the degree of brightness of the image," Thai said. "A brighter plant is a healthier plant."

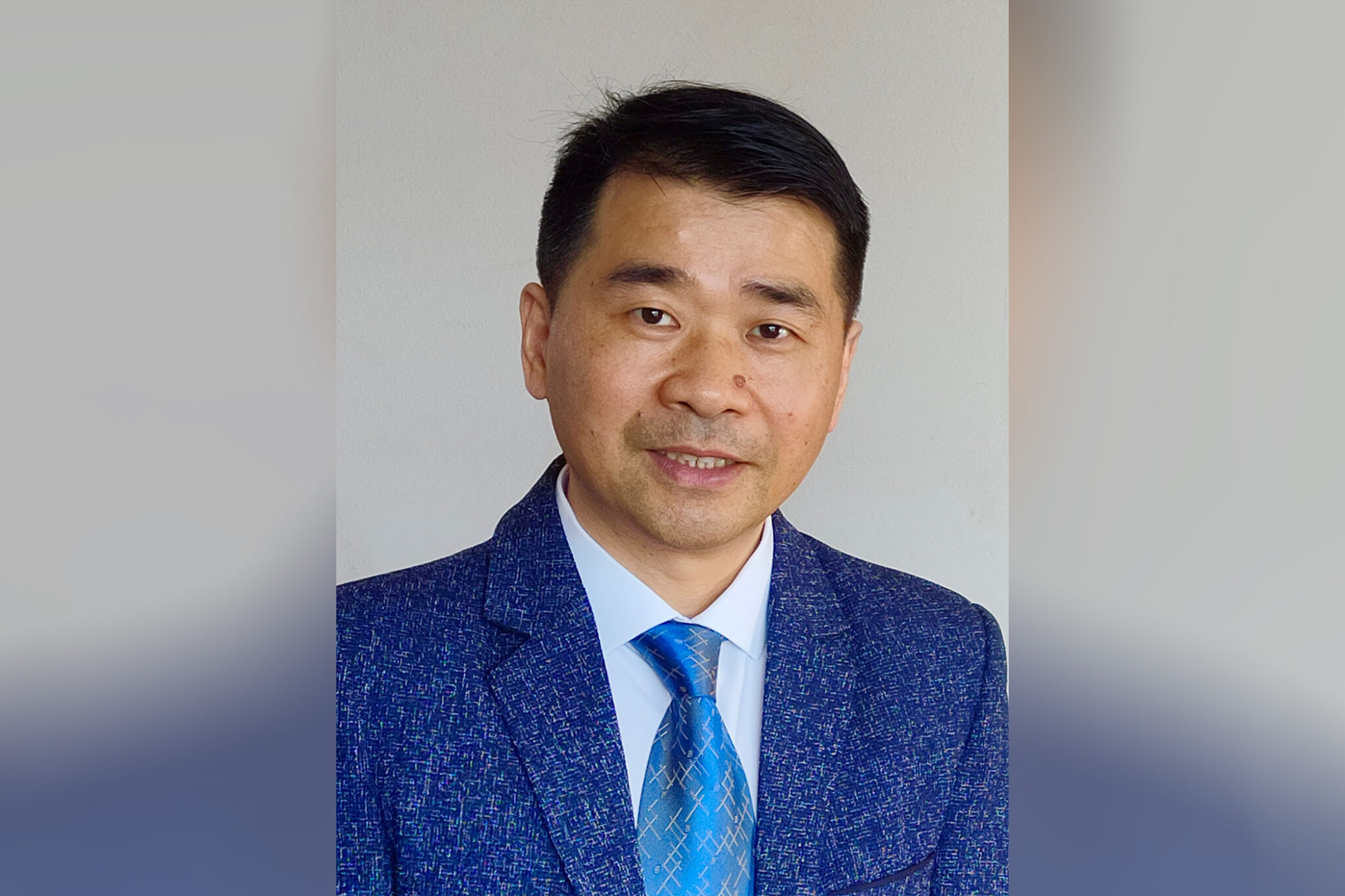

|

| The black-and-white images resulting from Thai's research show stark contrasts between the healthy plant on the left and the stressed plant on the right. |

Thai's initial, encouraging research was on Bahia grass and bush beans. Now he's studying peanut plants inoculated with Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus.

The biggest trouble so far has been getting the virus to infect the plants. "For some reason, what happens naturally very easily in the field has been hard for us to do in the lab," he said.

Research Could Help Growers

If the studies work, though, it could greatly help growers of the state's $400 million peanut crop, said Albert Culbreath, a CAES plant pathologist in Tifton, Ga.

"It would help first in research," Culbreath said. "It would be a nice tool for evaluating plants in greenhouse and small-plot studies."

Many plants don't show symptoms right away but turn yellow and wilt late in the season. "Such a tool might enable us to know what's really going on in those plants," he said.

"In epidemiological studies," he said, "detecting infection before symptoms occur might help pinpoint when management actions might be taken to reduce the ... disease."

Many Potential Benefits

Spectral imaging could help evaluate varieties and management practices, too. If it could help farmers assess disease problems faster than they can by seeing symptoms, it could help even more.

"If we could come up with a chemical signal for assessing problems that could be detected from a few feet above or a mile overhead," Culbreath said, "it could be of economic value."

It may help farmers boost their yields, he said. And even if it can't, it may be able to better predict losses, which would help growers in their marketing.

For the time being, all the scientists really know is the potential.

"We don't know what reality can be, or how much benefit," Culbreath said. "There's much work to be done, but new tools such as this can be of great importance in the future."