Knowing connection between drought, insect pests and aflatoxin empowers farmers

By Allison Floyd

University of Georgia, Peanut & Mycotoxin Innovation Lab

Drought can encourage aflatoxin buildup in peanut crops, but when farmers know about that risk, they can take steps to mitigate the problem.

“Farmers, when there is drought, can engage and be resourceful,” said Chancy Sibakwe, a Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources student who recently completed his master’s degree with support from the Peanut & Mycotoxin Innovation Lab.

Aflatoxins are the byproduct of a mold called Aspergillus flavus that can grow on corn, peanuts and other crops in the field and also during post-harvest storage. As researchers seek ways to minimize aflatoxin contamination, Sibakwe studied how much effect drought, pests, and disease can have on mold growth and aflatoxin contamination at the pod-filling stage of peanut development.

Using a greenhouse to control moisture, Sibakwe tested five peanut varieties at four levels of simulated drought – prolonged (4 weeks), minimal (3 weeks), mild (2 weeks) and no drought. Soil samples were collected from each plot at planting, beginning of drought, end of drought and at harvest. He also took samples of the nuts at harvest.

As he expected, drought significantly impacted mold in the soil and aflatoxin in the peanuts.

“When there is a longer period of drought, you should expect to have higher aflatoxin contamination, as well as higher A. flavus populations,” Sibakwe said.

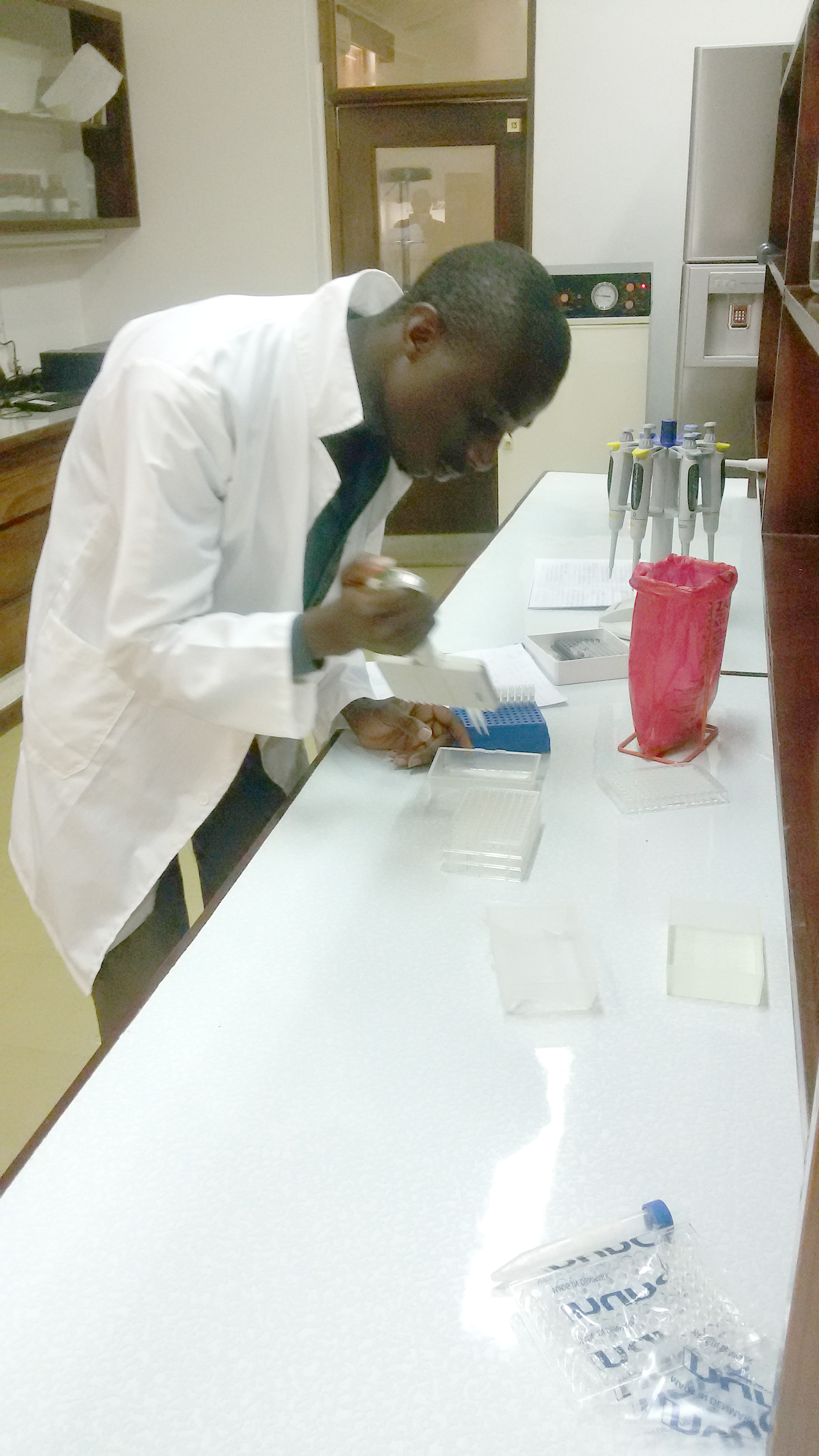

Chancy Sibakwe, a master's student at Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, works in the greenhouse where he tested the effect of drought and other stressors on aflatoxin development in peanuts.

Researchers know that drought and disease can lead to higher aflatoxin levels as infected plants are more susceptible to the mold that leads to contamination. In Sibakwe’s trials, the stress of drought led to higher and higher concentrations, leaving one plot – one of the varieties that was subjected to prolonged drought conditions – with 37 ppb of aflatoxin, more than 15 times the aflatoxin level in the same variety with no simulated drought. (For sake of the experiment, Sibakwe did not sort out visibly shriveled kernels, a task many farmers would do and which would likely lower the overall aflatoxin level.)

With variable climate and drought becoming more common, it is important for farmers to know when to irrigate or provide some other support to help the plant, Sibakwe said. They can’t invest resources without a return, but knowing how drought will affect their crop helps farmers make educated choices, he said.

To test the effect of biotic stresses – disease and insects – Sibakwe did trials with the same five varieties over two growing seasons in three areas of Malawi.

“When pests and diseases attack, they alter the physiological processes in the plant. This weakens the plant and makes it more susceptible to A. flavus. The plant also is more likely to produce weak pods which are then more susceptible to the mold,” Sibakwe said.

“When pests and diseases attack, they alter the physiological processes in the plant. This weakens the plant and makes it more susceptible to A. flavus. The plant also is more likely to produce weak pods which are then more susceptible to the mold,” Sibakwe said.

In different scenarios, he applied no chemicals, fungicides only, insecticides only, and both fungicides and insecticides, at three locations over two years.

As expected, the healthiest plants – highest yield and lowest aflatoxin levels – were those that received both fungicide and insecticide, while the plants with the poorest results – low yield and high contamination – received no chemical treatments.

But, the plants that received only insecticide had less aflatoxin contamination than the control group, again demonstrating how a plant weakened by insect damage is susceptible.

“It seems that insects can have a big impact on aflatoxin contamination,” Sibakwe said. “Farmers with few resources should at least consider applying insecticides to control insects as the results show that insects have an impact on increasing aflatoxin levels, as well as reducing the yield of groundnuts.”

The research also can help farmers know the importance of soil and water conservation measures and irrigating (if possible) during drought, Sibakwe said.

With a master’s degree completed, Sibakwe is now working as programs coordinator for the Catholic Development Commission in Malawi (CADECOM) under the Zomba Diocese Research and Development Department (ZARDD) in the southern city of Zomba. His job allows him to work toward food security by teaching farmers about growing techniques and empowering them to grow plentiful crops and build resilience to impacts of climate change.

He hopes to return to school in coming years to continue studies toward a PhD.

-Published May 31, 2017